Reference Information

Barrel/Tube Length: 69 inches

Bore: 3 inches

Weight: 1720 pounds

Weight figure is for gun carriage (900 lb) + tube (820 lb)

A private citizen, John Griffen, superintendant of the Phoenix Iron Co., Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, developed a system of making artillery in the 1850s that proved highly successful. His foundry took strips of wrought iron some ¾ of an inch wide and 4.5 inches thick and wrapped them by lathe around an iron core. In all, five layers were build around the core with a thin iron covering on top. Then the core was removed and a plug driven into the breech which not only closed the breech but also formed the cascabel. Then the mass was heated to welding temperature and up-set two inches in a press. It was rolled out from 4.5 to 7 feet and the bore was reamed out. Trunnions were welded on and the chase turned down to a proper size in a lathe.

The end result was a 3-in. rifled weapon with clean lines and light weight. It was made with 0.6-in.-wide lands and grooves that were 0.84 inches wide. The standard tube weight was 820 lb., although many were slightly lighter. Tests made during the war with a pound of powder and a 9-lb. shell at 10 degrees showed a range 2,788 yards, while a 20 degree elevation gave the weapon a range of 3,972 yards. It was also an exceptionally safe weapon: only one 3-in. rifle was recorded as having burst in the entire war (at the muzzle while firing double cannister during the Battle of the Wilderness) . Note that when first tested in 1856, the gun amazed the representatives of the Ordnance Department. Griffen himself challenged them to burst the piece. After more than 500 rounds with increasing charges and loads, they finally succeeded only by firing it with a charge of seven pounds of powder and a load of 13 shot which completely filled up the bore. It passed government tests and on June 25, 1861, the Ordnance Department ordered 200 rifled versions of this weapon, and another 100 smoothbores. In fact, the order was quickly changed to make all 300 weapons rifled, and eventually the Phoenix Iron Co. supplied the U.S. Army with 1,100 cannons by the war’s end. Each is marked on its muzzle with the inspector’s initials, the weapon serial number the weight, “PICo,” and the date of

manufacture.

These guns were popular with users in both sides . Brig. Gen. George D. Ramsay, Chief of Ordnance, reported that: “The experience of wrought iron field guns us most favorable to their endurance and efficiency. They cost less than steel and stand all the charge we want to impose on them…” Confederate artilleryman E. Porter Alexander jealously stated “The Yankee three-inch rifle was a dead shot at any distance under a mile,” and it was quite effective at a mile and a half. Though the Confederates obtained a few 3-in. rifles though capture, it was not until January, 1862, that the Tredegar Iron Works cast its first 3-in. rifle, and it produced a total of only 20, none of them after April, 1862. Noble Brothers & Co., Rome, Georgia, a private contractor, started manufacturing 3-in. rifles in 1861, producing 18 of them for both Richmond and Augusta Arsenals between April 1861, and October, 1862, when they ceased production Quinby & Robinson, of Memphis, Tennessee, another private venture, produced four versions of the rifle using bronze as the barrel metal between November, 1861, and June, 1862, when the city was captured by Federal forces. Bronze was also used as the barrel metal for the three 3-in. rifles produced by the A.B. Reading & Brother, Vicksburg, Mississippi, which saw use in the Army of Mississippi. The bronze versions were prone to bursting, and were known in the Confederate service as “Burton and Archers,” a term derived from the special ammunition designed for the guns.

The Ordnance Rifle, not to put too fine a point on it, was a nearly perfect field piece. The absolute epitome of muzzle-loading artillery, it remained the primary rifled field gun in the U. S. inventory well into the 1880's when it finally gave way to steel breechloaders.

Ammunition Used:

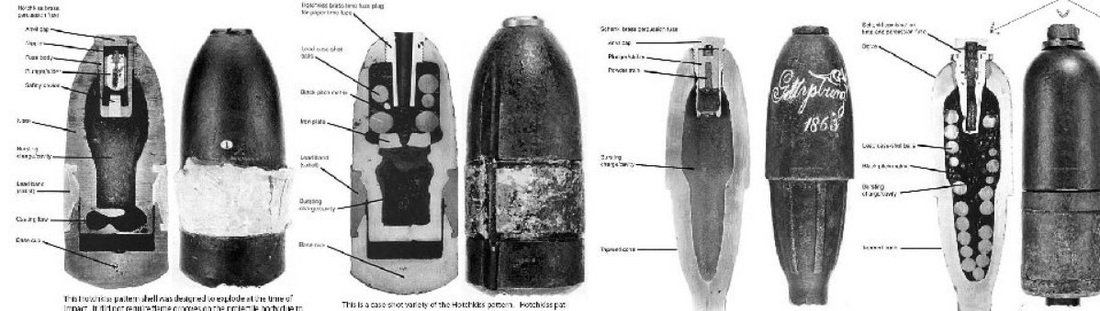

solid shot, case shot, common shell, cannister;

The 3-inch rifle normally fired Hotchkiss or Schenkel shells that weighed between 8 and 9 pounds. In an emergency it could use 10-pounder Parrot ammunition. It could also be used to fire cannister but, as a rifle, was not as effective with this as howitzers or Napoleons."

Bore: 3 inches

Weight: 1720 pounds

Weight figure is for gun carriage (900 lb) + tube (820 lb)

A private citizen, John Griffen, superintendant of the Phoenix Iron Co., Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, developed a system of making artillery in the 1850s that proved highly successful. His foundry took strips of wrought iron some ¾ of an inch wide and 4.5 inches thick and wrapped them by lathe around an iron core. In all, five layers were build around the core with a thin iron covering on top. Then the core was removed and a plug driven into the breech which not only closed the breech but also formed the cascabel. Then the mass was heated to welding temperature and up-set two inches in a press. It was rolled out from 4.5 to 7 feet and the bore was reamed out. Trunnions were welded on and the chase turned down to a proper size in a lathe.

The end result was a 3-in. rifled weapon with clean lines and light weight. It was made with 0.6-in.-wide lands and grooves that were 0.84 inches wide. The standard tube weight was 820 lb., although many were slightly lighter. Tests made during the war with a pound of powder and a 9-lb. shell at 10 degrees showed a range 2,788 yards, while a 20 degree elevation gave the weapon a range of 3,972 yards. It was also an exceptionally safe weapon: only one 3-in. rifle was recorded as having burst in the entire war (at the muzzle while firing double cannister during the Battle of the Wilderness) . Note that when first tested in 1856, the gun amazed the representatives of the Ordnance Department. Griffen himself challenged them to burst the piece. After more than 500 rounds with increasing charges and loads, they finally succeeded only by firing it with a charge of seven pounds of powder and a load of 13 shot which completely filled up the bore. It passed government tests and on June 25, 1861, the Ordnance Department ordered 200 rifled versions of this weapon, and another 100 smoothbores. In fact, the order was quickly changed to make all 300 weapons rifled, and eventually the Phoenix Iron Co. supplied the U.S. Army with 1,100 cannons by the war’s end. Each is marked on its muzzle with the inspector’s initials, the weapon serial number the weight, “PICo,” and the date of

manufacture.

These guns were popular with users in both sides . Brig. Gen. George D. Ramsay, Chief of Ordnance, reported that: “The experience of wrought iron field guns us most favorable to their endurance and efficiency. They cost less than steel and stand all the charge we want to impose on them…” Confederate artilleryman E. Porter Alexander jealously stated “The Yankee three-inch rifle was a dead shot at any distance under a mile,” and it was quite effective at a mile and a half. Though the Confederates obtained a few 3-in. rifles though capture, it was not until January, 1862, that the Tredegar Iron Works cast its first 3-in. rifle, and it produced a total of only 20, none of them after April, 1862. Noble Brothers & Co., Rome, Georgia, a private contractor, started manufacturing 3-in. rifles in 1861, producing 18 of them for both Richmond and Augusta Arsenals between April 1861, and October, 1862, when they ceased production Quinby & Robinson, of Memphis, Tennessee, another private venture, produced four versions of the rifle using bronze as the barrel metal between November, 1861, and June, 1862, when the city was captured by Federal forces. Bronze was also used as the barrel metal for the three 3-in. rifles produced by the A.B. Reading & Brother, Vicksburg, Mississippi, which saw use in the Army of Mississippi. The bronze versions were prone to bursting, and were known in the Confederate service as “Burton and Archers,” a term derived from the special ammunition designed for the guns.

The Ordnance Rifle, not to put too fine a point on it, was a nearly perfect field piece. The absolute epitome of muzzle-loading artillery, it remained the primary rifled field gun in the U. S. inventory well into the 1880's when it finally gave way to steel breechloaders.

Ammunition Used:

solid shot, case shot, common shell, cannister;

The 3-inch rifle normally fired Hotchkiss or Schenkel shells that weighed between 8 and 9 pounds. In an emergency it could use 10-pounder Parrot ammunition. It could also be used to fire cannister but, as a rifle, was not as effective with this as howitzers or Napoleons."